University of Ljubljana

REFORMING THE RELEATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARTICIPANT AND RESEARCHER:

SECOND-PERSON IN-DEPTH PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY

The core credo of our research is the premise that the most precise »instrument« for researching experience is an interested observer well versed in reflection. We do not see first-person research as the extraction of information from a subject, but as the process of 1) a co-researcher observing their own experience and 2) joint articulation and participatory sense-making.

Second-person in-depth phenomenological inquiry (SIPI) is based on this credo. It is designed so as to encourage and empower subjects, so that through the process of dialogical research they become expert researchers of their experience and join, as equal investigators, our research team in answering the research question.

SIPI is an interview-based technique that can be used to study virtually any experienced cognitive phenomenon. The technique is grounded in what we consider to be two most promising interview methods for exploring experience so far developed within the field of cognitive science: Russell Hurlburt's descriptive experience sampling method (Hurlburt, 2011) and Claire Petitmengin's method of micro-phenomenological interviewing (Petitmengin, 2006). So far, we have applied SIPI to investigate phenomena related to belief and knowledge enaction (Kordeš & Klauser, 2016).

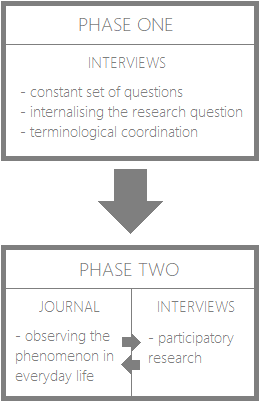

SIPI is divided into two phases. In phase one, after specifying the research question and selecting the studied experiential phenomenon, a higher number of interested participants take part in a series of interviews about experience. This serves three important functions:

1. Attaining a coarse understanding of the selected experiential phenomenon, which enables us to further specify the direction of the study.

2. Introducing participants (who may not be previously trained) to the process of researching experience.

3. Selecting, from a higher number of participants, a smaller group of co-researchers to be invited to continue to phase two. Delving into one’s own experience is a challenging (and not always pleasant) endeavor, and doing it right requires a considerable amount of time and dedication. Only those participants can become reliable (and not too frustrated) co-researchers who show a strong interest in investigating their experiential landscape as well as a commitment to further thorough analytical work.

By the beginning of phase two, a handful of selected co-researchers have already familiarized themselves with the research process and internalized the project's research question as their own. They can now begin observing the selected experiential phenomenon in their everyday life, and note any relevant observations in their experiential journal. Over the course of the study, the journal notes serve as a starting material for a series of interviews aimed at further exploring interesting experiential moments. The interviews are carried out in a participatory spirit, taking the form of a cooperative research dialogue in which the researcher and co-researcher jointly investigate significant parts of the co-researcher's experiential life.

The results of this dialogical process – a process akin to what Hanne De Jaegher and Ezequiel Di Paolo (2007) call participatory sense-making – are inevitably co-constructed by both involved parties. Most importantly, these co-constructions at no point amount to final answers, but keep evolving throughout the course of the study. The sequential analysis of acquired empirical data continuously guides the direction of research, enabling the research team to re-examine and re-shape their previous views and ask new questions regarding the studied phenomenon. What is discovered in a particular interview session will, for instance, direct the co-researcher in her following observations and journal entries; conversely, these journal entries serve as a foundation for further interview sessions that may again lead to new discoveries. Moreover, findings from working with one co-researcher can be compared with findings from other co-researchers, which can again influence further research.

REFERENCES

De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E. (2007). Participatory sense-making. Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences, 6(4), 485-507.

Hurlburt, R. T. (2011). Investigating Pristine Inner Experience: Moments of Truth. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kordeš, U. & Klauser, F. (2016). Second-person in-depth phenomenological inquiry as an approach for studying enaction of beliefs. Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems: INDECS, 14(4), 369-377.

Petitmengin, C. (2006). Describing one’s subjective experience in the second person: An interview method for the science of consciousness. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 5(3–4), 229–269.